The Hidden Clocks Inside Us

Rea,

You mentioned how hard it is to fall asleep during summer when it’s still light outside at bedtime. That struggle you feel isn’t just in your head - it’s your body’s hidden clock system working exactly as designed.

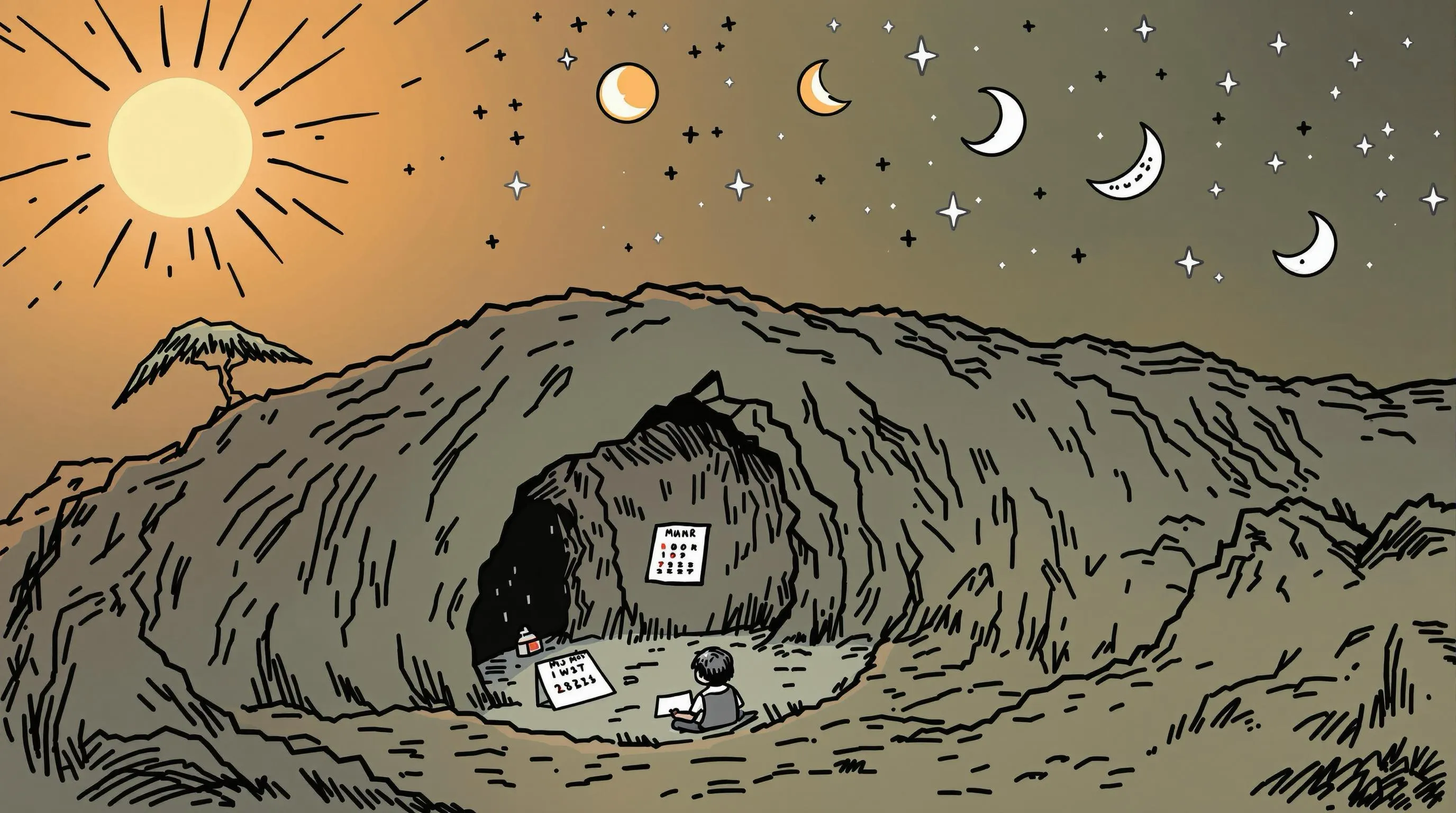

In 1962, a French scientist named Michel Siffre decided to conduct one of the most extreme experiments in human history. He descended into a dark cave in the French Alps and stayed there for two months - 63 days - without any clocks, sunlight, or time cues whatsoever. No phone, no watch, no way to tell if it was day or night above ground.

Siffre wanted to discover what would happen to his sleep schedule without any external signals. Would his body just give up on having a routine? Would he sleep randomly throughout the day?

Something interesting happened. Even in complete darkness, Siffre’s body maintained a regular sleep-wake cycle. He would feel alert for about 16 hours, then naturally become sleepy and sleep for about 8 hours. His body had settled into a rhythm of approximately 25 hours - close to, but not exactly, a 24-hour day.

This experiment proved that humans have an internal biological clock that works independently of sunlight. Scientists later discovered this “master clock” sits in a tiny region of your brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus - about the size of a grain of rice but controlling the timing of your entire body.

Siffre’s discovery revealed how this system works: When light hits your eyes, special cells send signals to your brain’s master clock. Bright light says “stay awake,” while darkness triggers production of melatonin - a hormone that makes you feel drowsy and ready for sleep.

During summer, daylight lasts until 8 or 9 PM, so your brain keeps getting “stay awake” signals long past your normal bedtime. This problem gets even trickier for teenagers - their internal clock naturally shifts later during adolescence, with melatonin production starting around 11 PM instead of 9 PM. Summer light plus teenage biology creates the perfect storm for late bedtimes.

Siffre’s experiment helped scientists understand why jet lag feels so disorienting and why some people struggle more with shift work than others. It also explained why you might feel groggy during your first few days in Scotland or India - your internal clocks need time to adjust to new time zones.

Your body runs dozens of these quiet timekeepers. Your core temperature drops right before you feel sleepy. Your reaction time peaks in late afternoon. These rhythms keep running whether you’re in a bright room or Siffre’s dark cave, constantly keeping time even when you’re not paying attention to any actual clocks.

Love, Abba